This page presents a summary of Diane Thomas's original research article. The full article, published in Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 136 (2015), is available for download above.

Overview

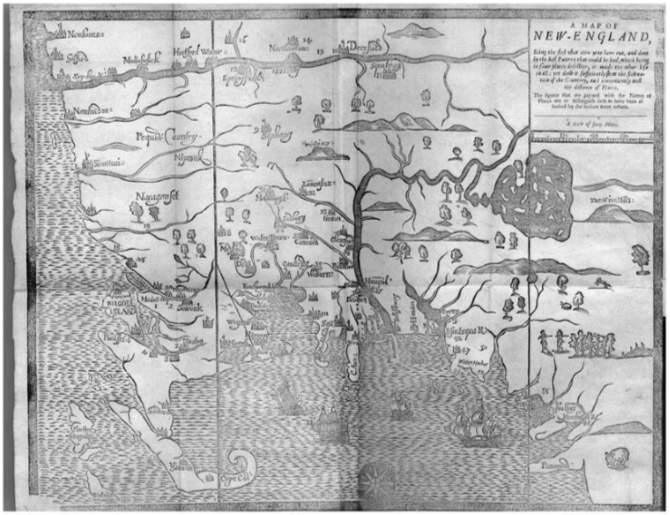

The Hercules sailed from Sandwich, Kent to New England in March 1634, carrying 102 passengers. This voyage occurred during the "Great Migration," which saw an estimated 20,000 English people emigrate to New England between 1628 and 1640. The Hercules was unique among emigration ships: it was one of only two known ships to sail from Sandwich (most sailed from London), and with one exception, all passengers were from Kent. The ship itself was jointly purchased by several passengers, making it a collaborative venture rather than a commercial operation.

The Passengers

The Hercules carried a remarkable group of passengers. Many had distinctive Puritan names that signaled their religious radicalism: Comfort Starr traveled with his sister Truthshallprevail; their siblings included Jehosephat, Nostrength, Moregifte, Suretrust, Standwell, Constante, Joyful, and Beloved. Nathaniel Tilden, a key figure, had brothers named Hopestill and Freegift. Another passenger was named Faintnot Wines.

Among the passengers were also skilled tradesmen, including Thomas Bonney and Henry Ewell, both shoemakers from Sandwich. Thomas Bonney would go on to become the founding patriarch of the Bonney family in America, settling in Duxbury, Massachusetts, where he served as constable, surveyor of highways, and participated in King Philip's War, earning a land grant for his military service.

Unlike typical emigrant groups of the period who were predominantly young, male, and unmarried, the Hercules passengers more closely resembled the general English population. Nearly 72% traveled in family groups, with 64% in nuclear families—similar patterns to other "Great Migration" ships. The passengers included people of significant standing: Nathaniel Tilden had been mayor of Tenterden in 1622; William Witherell was an ordained clergyman; Comfort Starr was a surgeon and grandson of the mayor of New Romney; Robert Brooke was a mercer; and William Hatch was a merchant.

Education levels were notably high. Four families had university connections: William Witherell graduated M.A. from Corpus Christi, Cambridge; Freegift Tilden (Nathaniel's brother) attended Cambridge; Theophilus Tilden (another brother) matriculated at Oxford; and Comfort Starr's father had attended Emmanuel College, Cambridge. Many passengers came from towns with established grammar schools, and probate inventories reveal substantial book collections among the passengers, indicating high literacy rates.

Key Connections

Nathaniel Tilden emerges as the central figure who organized the voyage. He was listed first on the passenger manifest, was part-owner of the ship, and had the most connections to other passengers. Remarkably, Tilden was step-brother to Robert Cushman, who had negotiated the patent for the Mayflower voyage in 1620. Tilden's brother Joseph was one of the financiers of the Mayflower. Tilden himself had purchased land in Scituate, Massachusetts before 1628, suggesting he may have been an investor in the colony as well as a settler.

The passengers were extensively interconnected through family and friendship ties. The Tilden, Hatch, Austen, and Besbeech families were particularly linked. Many passengers also had close family members who traveled separately to New England, creating a web of connections that extended beyond the single voyage.

Motivations: Religion, Economics, and More

Diane Thomas's research challenges the traditional view that the "Great Migration" was purely a religious exodus. While many Hercules passengers clearly had radical religious sympathies—evidenced by their names, book collections (including works by leading Puritans), and connections—the evidence suggests religion was not always the primary or sole motivation.

The timing of the migration (1628-1640) exactly coincided with the rise and fall of anti-Puritan Archbishop William Laud, providing circumstantial support for religious motivations. However, Thomas found little evidence of actual persecution among the Hercules passengers. Most had certificates of conformity signed by local authorities, and ecclesiastical court records show only minor matters like disputed wills and non-payment of tithes—not severe persecution. Only Comfort Starr appears on a schedule of excommunicated individuals, and even that was from 1618, well before the voyage.

Economic factors were also present but complex. While Kent and East Anglia (where many emigrants originated) were cloth-producing areas experiencing decline, Kent suffered less than other regions due to "New Draperies" and emerging industries. The cost of emigration was substantial—passage, supplies, and seed money would have been prohibitive for those in genuine economic distress. Instead, many Hercules passengers were comfortably-off individuals seeking new economic opportunities rather than escaping hardship.

Other potential motivations included: fear of epidemics (Sandwich had outbreaks of smallpox in 1624 and plague in 1625); peer pressure to stay with family and friends; desire for political and educational freedom; escape from various personal problems; and the appeal of adventure and opportunity in a new colony.

The Ship and Sandwich

The Hercules was a 200-ton Flemish-built ship, previously named St Peter, purchased for £340 at Dunkirk in November 1634. It was jointly owned by Comfort Starr, Nathaniel Tilden, William Hatch, John Witherley (the ship's master), and a Mr. Osborne. If the owners charged standard rates (£5 per adult), they would have raised £300-£350 in one voyage, covering their initial investment. However, wills and inventories show no mention of the ship after arrival, suggesting the venture was short-lived.

Conclusion

Thomas's research reveals that the Hercules passengers, while typical of "Great Migration" emigrants in many ways, had distinctive characteristics: close links to civic elites, high educational levels, extensive interconnections, and strong connections to key figures in Plymouth Colony's early history. The evidence suggests that motivations were complex and intertwined—religion was often present but not always primary. Many emigrants were seeking new opportunities and a new community rather than simply fleeing persecution or hardship. Nathaniel Tilden, with his unique range of contacts and his early presence in New England, may have been a key motivator behind the migration wave that began in 1634.

The research supports the view that emigrants' motives were "historically inseparable"—a complicated mix that cannot be easily categorized as purely religious or purely economic, but rather reflected a desire for a new life in a new community where they could exercise greater control over their own destinies.

Read More: Thomas Bonney | Sandwich, England | Family History Timeline | All Articles